What are climate targets worth?

Over the past decade, EU climate policies and global climate conferences have given the impression that their success depended on announcing ever-higher climate targets. The EU delegation at COP26 expressed disappointment that no new groundbreaking targets could be agreed upon to raise current climate goals. Unfortunately, European climate and environmental policy tends to focus too much on setting ambitious targets and too little on the policies to achieve them.

The European greenhouse gas (GHG) reduction targets for 2030 are a good example. Originally, the EU set a 2030 GHG reduction target of -43% for energy-intensive industries, then increased it to -61%, and two years later changed it again to -62% (all compared to 1990). Most energy-intensive industries are subject to the EU Emissions Trading Scheme (EU ETS). Under this system, companies must purchase allowances for their greenhouse gas emissions. This gives them an incentive to invest in reducing emissions. However, frequently changing targets are not conducive to planning and investment security; they make it difficult for companies to assess whether their GHG reduction investments will meet the targets and yield a return.

Also, GHG reduction targets in non-ETS sectors are prone to inflationary objective setting. These include transportation, buildings, agriculture, and waste sectors, for which a reduction target of -30% compared to the 2005 levels was initially set. A few years later, this target was raised to -40%. Frequently changing and increasingly ambitious targets also apply without exception to renewable energy, energy efficiency, green hydrogen, or waste reduction policies.

While the industry recognizes that the climate crisis requires ambitious targets, it would serve the cause better to focus less on the targets and more on their implementation. In other words, the announcement of ambitious climate goals must be followed up by equally ambitious policy instruments. We observe, however, that while targets increase, framework conditions and policy instruments often are unchanged or fail to match the ambitions. The result is a widening gap between ambitions and the climate performance of stakeholders. This is challenging for both businesses and politics and discredits the value of climate targets.

Climate targets in Luxembourg

The final balance of greenhouse gas emissions for the year 2021, published by the Ministry of the Environment on March 15th, 2023, notes that not all of Luxembourg’s sectors are on track to meet the 2030 climate targets. Indeed, the construction and industrial (non-ETS) sector has difficulty staying on the trajectory. At the same time, this does not come as a surprise, as Luxembourg decided in 2021 to set its target at -52% GHG emission reduction compared to 2019. This is one of the most, if not the most ambitious target for this sector at the entire EU level.

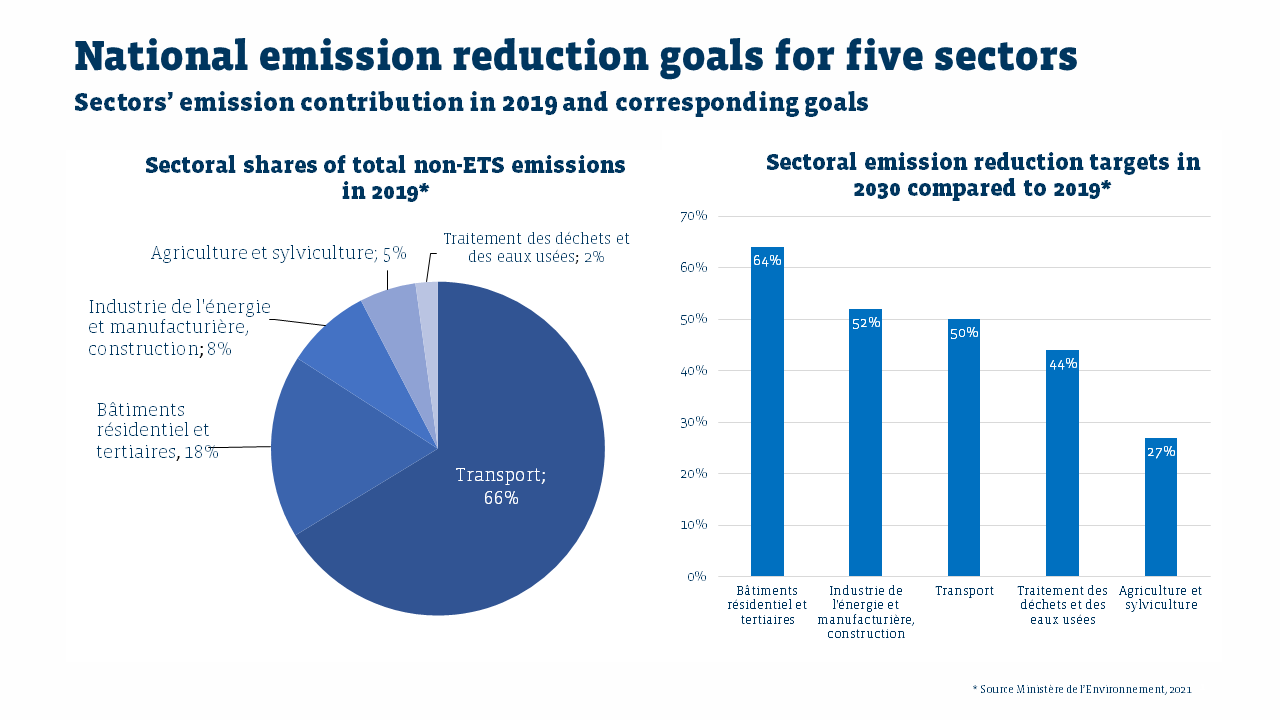

The diagrams in Figure 1 show Luxembourg’s emission reduction targets for the five non-ETS sectors compared to 2019. All sectors together are supposed to reduce emissions by 51% compared to 2019, for the industrial sector, a reduction of 52% compared to 2019 is required.

France’s 2030 target for greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions reduction in this same industrial sector is -35% compared to 2015, and Germany’s is -31% compared to 2020. The years of reference of the three countries’ objectives differ by five years, yet the discrepancies of over 20% compared to Luxembourg stays. Neither France nor Germany’s targets are even close to what Luxembourg wishes to achieve until 2030.

At this point, one might wonder what evidence the national government had found to establish such excess GHG emission reduction potential in Luxembourg’s industry compared to Germany and France.

Evidence-based target setting is needed

FEDIL and its members support the Luxembourg government’s climate and environmental protection aspirations. Within FEDIL’s membership, there is a large consensus that the industry wants to contribute to climate protection. At the same time, members agree that evidence-based target setting is critical to set realistic climate goals. Also, only evidence-based target setting enables policymakers to assess and design the measures to close the gap between targets and the current situation.

Unfortunately, the government only presented a study analyzing the decarbonization potential of Luxembourg’s industry in December 2022, one and a half years after the sectoral reduction targets had been defined1. The study identified 69 decarbonization projects in Luxembourg’s manufacturing industry (ETS and non-ETS), out of which it quantified the most significant 40 projects. The study estimates that Luxembourg’s non-ETS manufacturing industry’s decarbonization potential until 2030 is only around -13% instead of the targeted -52%. The same goes for the ETS, whose potential is around -33% instead of the EU target of -62%.

The findings of this study confirm that while Luxembourg has adopted an ambitious climate policy, it has yet to implement measures that would effectively incentivize companies to undertake energy transition projects with higher decarbonization potential. As the government prepares to submit an updated national energy and climate plan to Brussels by the end of 2023, it should use the opportunity to enhance climate measures that support low-performing sectors, enabling them to achieve their targets.

Europe’s climate policy needs a paradigm change

FEDIL, representing almost 700 members of the Luxembourg industry, endorses the EU’s 2030 and 2050 climate objectives. The industry acknowledges its responsibility and vital role in facilitating the energy transition’s success. Nevertheless, it faces an immense challenge as a considerable portion of current production facilities requires significant upgrades or complete replacement to shift from fossil fuels to renewable sources. The present framework conditions are ineffective in making the related investments viable. For the time being, they would endanger the firms’ global competitiveness and prospects.

Instead of incentivizing change, however, the EU’s climate policies emphasize restrictions, limitations, and penalties. These increase the cost of compliance, contribute to investment uncertainty, and make it more difficult for companies to embark on the energy transition journey. We observe a recurring pattern in the EU’s climate policy: first, it unilaterally sets high restrictions costing many sectors a large part of their international competitiveness, only to restore it partially through exemptions, subsidies, and other support. The EU’s Emissions Trading System (ETS) or the Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanism are synonyms for this pattern. The many aspects of climate policy set restrictions so high in many industries that doing business in Europe without subsidies has become unprofitable.

We believe that ever-increasing climate goals and rising restrictions and limitations cannot tackle the energy transition. Instead, the energy transition’s success depends mainly on Europe’s ability to create framework conditions that attract low-carbon investment by giving them a solid and long-term perspective on return. Such a framework cannot be based on subsidies alone. It must rather be stitched around a comprehensive European industrial strategy that encompasses issues such as the security of competitively priced renewable energy supply, access to raw materials, development of local manufacturing capabilities, accelerating planning and permit-granting procedures, the global competition for talents, and financing technological innovation, and green growth.

What elements make IRA attractive for EU companies?

The Inflation Reduction Act (IRA) of the Biden Administration made the EU finally realize that its climate policy could also be less restrictive and, above all, less expensive and burdensome for businesses. Unlike its name suggests, this act has little to do with reducing inflation. It is the most extensive package of climate spending in the history of the United States, a law worth around $400bn of subsidies and tax credits over a decade. It promotes renewable energy, hydrogen production, electric vehicles, carbon capture and carbon capture and storage, batteries, and more.

The U.S. administration expects the IRA to close two-thirds of the greenhouse gas emissions gap between the current policy and the United States 2030 climate goal. Further, by decreasing the development and deployment costs of clean energy, the IRA would also allow to close the remaining gap more cost-effectively and rapidly. The IRA’s energy and climate subsidies fall into three categories; they apply mainly to two industries, clean energy, and semiconductors:

Subsidies for passenger and commercial vehicle purchases, including consumer tax credits for electric cars and tax credits for companies, including leasing companies, that buy clean vehicles.

Production and investment subsidies for manufacturers of clean-tech products, including batteries, components used in renewable electricity generation, and critical materials like aluminum, cobalt, and graphite.

Subsidies for producers of carbon-neutral electricity. Subsidies are either in the form of production cost subsidies or investment tax credits. These incentives also support rural and residential green electricity production and nuclear energy production. Finally, the production of hydrogen and clean flues are eligible for subsidies.

At first sight, EU economies might be alarmed by the eye-watering amount the US unblocked to make their lagging climate efforts catch up with the EU’s. However, a more detailed analysis reveals that the EU’s multiple climate initiatives at the European and Member State levels pour out similar sizes of green subsidies. In renewable energy production, EU subsidies are even more significant.

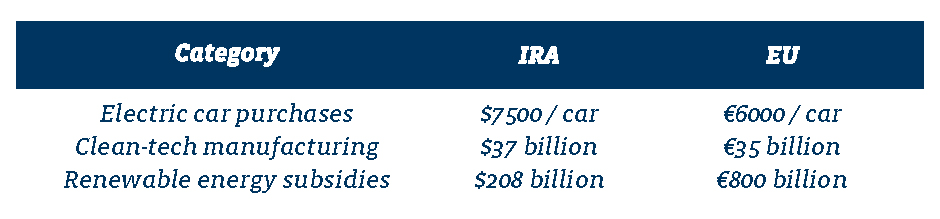

Table 1 shows a projected assessment by Bruegel, a Brussels-based thinktank comparing the three main categories of IRA green subsidies with EU subsidies that serve broadly similar purposes. The authors make a disclaimer to use the table as illustrative, considering the many assumptions and uncertainties of the projection.

The takeaway from the table is that IRA and EU subsidies in those three categories can be considered at the same level, except for renewable energy production, assuming the EU and its Member States continue to subsidize at the same rate as in recent years.

According to Bruegel, the main difference between IRA and EU subsidies is not the size, except for renewable energy, where Europe would still lead. IRA differs most from EU subsidies in the following three points: First, some IRA subsidies discriminate against foreign producers while EU subsidies do not. Second, the IRA’s clean-tech manufacturing support is more straightforward than the EU’s, offering tax credits for an entire decade. Conversely, the EU support in this field is fragmented, slower, and bureaucratic, and it also has a shorter-term impact, requiring projects to be handed in by the end of 2025 if they wish to receive financial support. Third, the IRA prioritizes the large-scale implementation of existing clean technologies, whereas the EU tends to concentrate on promoting innovation and early-stage adoption of new technologies.

The following paragraph picks up the promotion of clean hydrogen as a typical example illustrating how differently the EU and the US’ IRA approach the issue.

Clean hydrogen in the EU – Why make it simple when it can be complicated?

While the EU imposes strict specifications and complicated requirements for the electricity used to run clean hydrogen electrolysis, the IRA does not have such restrictions. It succeeds in promoting clean hydrogen in a much straighter manner.

Under the IRA, clean hydrogen plants can receive, already in 2023, a production tax credit of up to $3 per kg of produced hydrogen, depending on the carbon emissions involved in the production, for the first 10 years of operation. The less carbon emission hydrogen production entails, the more support it gets. The tax cuts run through 2032, encouraging projects to start early to ramp-up hydrogen production rapidly. Projects starting in 2023 would benefit from the entire 10 years’ worth of credits, while plants opening later would receive progressively less. The IRA offers multiple benefits to producers of green hydrogen, including pretty generous provisions. Firstly, those who produce green hydrogen using renewable electricity are eligible for both tax credits, for producing renewable power and for producing hydrogen. Moreover, for the initial five years of operation, the hydrogen tax credit is a « direct pay, » implying that clean hydrogen producers can receive a tax refund equal to the worth of their tax credits. Additionally, clean hydrogen and renewable electricity producers can use « transferability » tax benefits, meaning that producers with no tax liability can sell their tax credits to purchasers with tax obligations.

As contrast, the EU only recently defined in the “delegated acts” the conditions for hydrogen to be accepted as green: This new regulation requires that renewable hydrogen be produced only with additional, i.e. newly, dedicated and directly connected renewable electricity generation equipment or if not directly connected that the hydrogen be produced only during the hours that the renewable electricity generation equipment is producing electricity (hourly temporal correlation) and only in the area where the renewable electricity generation equipment is located (geographic correlation). Further, grid electricity may be used to produce renewable hydrogen without further restrictions only if the renewable energy share in the grid has exceeded the 90% threshold in one of the last five calendar years. As a reference, in 2021, Sweden had the highest share of renewable energy, with around 60% renewables, while the EU average is at around 23%. All these restrictions are not only complicated to fulfill, but they inevitably make green hydrogen projects scarce and more expensive than in the US, limiting the potential for a rapid expansion of the clean fuel in Europe. They reduce the positive impact of economies of scale and might even risk compromising Europe’s ability to meet its production targets. Considering all these limitations and restrictions, the EU Commission has granted a transition period until 2028 for the additionality condition and 2029 for the temporal correlation. In contrast, IRA will grant subsidies for clean hydrogen already in 2023, no exceptions or transition periods are needed.

There is a considerable risk that Europe will not be able to rapidly ramp up its clean hydrogen production enough to comply with its climate goals. The consequences could be gloomy. On the one hand, we can expect that Europe will have to import huge volumes of hydrogen from third countries. Such imports will not only create a new energy dependency, much like the one we know from Russian gas. It also risks slowing the expansion of Europe’s local production capacities because the less constrained, imported hydrogen may be cheaper than the one produced in Europe.

On the other hand, Europe risks losing significant parts of its industry from sectors that are hard to decarbonize without access to competitively priced and securely available clean hydrogen. Steel and aluminum makers, cement producers and glass manufacturers might decide to relocate their productions in parts of the world that provide direct and unconstrained access to cheap, clean hydrogen and export their goods to Europe instead.

Does IRA work?

For many years, Europe boasted of being the global leader in climate policy. One might wonder whether the US’ much more recent initiative stands a chance against Europe’s first mover advantage. Hence, does the less complicated, more straightforward, and bolder approach to climate policy pay off? Does IRA work? The answer is yes, it does!

The Economist, a British weekly newspaper, reports that since the IRA was enacted in August 2022, First Solar, a solar panel manufacturer, has announced plans to expand production in Ohio and build a new factory in Alabama. In January 2023, Hanwha Qcells announced it would spend $2.5 billion to increase its Georgia production fivefold. Chipmakers have announced a similar wave of investment: $200 billion spread across 16 states. TSMC, a Taiwanese company, is building a new factory in Arizona, Intel one in Ohio, and Micron one in New York. Smaller companies that supply these chipmakers also have big plans; dozens of chip suppliers are reportedly looking for suitable locations.

At the same time, the Financial Times, a British daily newspaper, reports no later than in March that the German car manufacturer VW put a planned battery plant on hold in eastern Europe as it evaluates support opportunities by IRA and waits to see how the EU would respond to Washington’s incentives.

The European response to IRA and what it means for Luxembourg

At first, the EU showed deep concerns about the protectionist elements of the IRA, which includes potential trade distortive subsidies. With its local content requirements, IRA ignores some of the most fundamental rules of the World Trade Organization regarding free trade. One of these requirements is, for example, the origin of the raw materials used in batteries to be eligible for subsidies. The IRA mandates that 40 percent of a battery’s critical minerals must come from the U.S. or a country with which the U.S. has a free trade agreement. Those countries are Canada, Mexico, and Japan since only very recently. By 2027, locally produced raw materials should increase to 80 percent. The EU could have been among the beneficiaries, but the TTIP negotiations to create a transatlantic trade zone failed in 2017. This excludes European manufacturers from US subsidies. Fearing investments would flow away to the USA, the EU sent high EU-level delegations to Washington. Also, the German Chancellor, Scholtz, and France’s President, Macron visited President Biden, trying to open the door for a broader range of U.S. allies to qualify as trading partners.

Such concern is well founded; according to the German newspaper Handelsblatt, the Swedish battery cell manufacturer Northvolt has halted plans for a factory in Germany for the time being and wants to expand its business in the U.S. Tesla has also scaled back its plans to build batteries in its German operation near Berlin. Except for a few concessions to Europe, the USA did not substantially change the nature of the IRA, so the risk of investment leakage is real.

Europe must finally recognize that it needs to change its climate policy to become more cost-effective and business-friendly. Its ambition must be to reach the same climate goals but less expensively. Failing to do so will drain much-needed low-carbon investment to regions with less costly climate frameworks, lower energy prices, and more attractive subsidies. This is what the USA and IRA are.

For a considerable duration, Europe’s climate policy was implemented without sufficient consideration of the potential impact on businesses’ ability to comply and remain profitable. As a result, Europe’s businesses have accumulated significant international competitive disadvantages over the past two decades. Geopolitical instabilities are currently amplifying them.

By the end of 2022, the EU Commission launched multiple initiatives to address the competitiveness issue and the risk of investment outflows. These initiatives include a reform of the electricity market design to reduce power prices, a critical raw materials act to ensure an adequate supply of rare earth minerals, an updated version of its temporary framework to address high energy prices, and the EU Net Zero Industry Act,

which represents the EU’s most direct response to the issue of IRA.

The Net Zero Industry Act aims to promote clean technologies within the EU and equip it for the clean-energy transition. Its objective is to strengthen the resilience and competitiveness of net-zero technology manufacturing, enabling EU companies to produce components and solutions for renewable energy generation, batteries, heat pumps, electrolyzes and fuel cells, grid technologies, carbon capture technologies, and many more. It aims to create better conditions to set up more rapidly such net-zero projects in Europe and attract investments. It wants the Union’s overall strategic net-zero technologies manufacturing capacity to approach or reach at least 40% of the Union’s deployment needs by 2030.

The regulation sends a clear political signal that the EU wants to develop its manufacturing capacity for the energy transition, but there… it stops.

Unfortunately, again, the Net Zero Industry Act falls into the same trap as the EU’s climate policy. It sets ambitious goals but fails to provide the means to implement them effectively. For example, the Net Zero Industry Act does not touch any existing EU legislation known to slow down the permit-granting process for new industrial projects, nor does it fundamentally change the financing options for the technologies it seeks to promote. While it proposes that permit-granting processes in dedicated zones be issued within 12 months for compliant projects, we know that permitting processes are under the jurisdiction of EU Member States. So, without a specific provision at the EU level allowing or encouraging Member States to speed up permitting procedures, this goal is no more than a wish that will probably never materialize.

Member States need to understand that they probably can no longer count on a coordinated European response to the IRA; they must act on their own to avoid industrial investments from flowing out of their counties. The Net Zero Industry Act provides the narrative but does not go further, so it’s up to each Member State to seize the opportunity and position itself within this narrative. It is an opportunity but even more so a responsibility if we are serious about making the energy transition a reality.

As one of the EU’s Member States that strongly and repeatedly emphasizes its climate ambitions, Luxembourg can now demonstrate leadership by adopting a clear profile and welcoming net-zero manufacturing capacities. As a country stressing the importance of renewables and condemning those that settle for the low-carbon instead, Luxembourg must accept that it has the moral obligation to contribute to developing net-zero technologies. Further, reaping a first-mover advantage is essential for Luxembourg as a small country. With limited space to welcome new clean industries and insufficient renewable energy to power them, it must focus on securing non-energy-intensive yet high-value-added net-zero technology and components productions that can be manufactured independently from a large land area.

The vicious cycle of de-industrialization

Years of a cost-ineffective and restrictive EU climate policy gave IRA an easy game in creating Europe’s new green competitor across the Atlantic overnight. Indeed, IRA may be heralding a turning point in Europe’s future prosperity perspective and its ability to succeed in the energy transition: If Europe would lose significant investments into crucial future technologies such as batteries, renewable power generation, electrolyzes, or carbon capture to the U.S., its economic future may be at stake.

The EU’s New Green Deal, presented in December 2019, described the energy transition as an economic growth opportunity for Europe. Trusting that businesses would find solutions, the EU Commission steadily increased climate regulations in the past. However, if we now fail to make clean technologies part of EU economies, the energy transition will not prove to be an opportunity but rather a heavy burden. Without proper competencies and access to clean technologies, Europe’s economies will be unable to overcome the many self-inflected climate regulations. The missing technologies would need to be expensively imported, making the energy transition an economic and social nightmare rather than an opportunity.

Eventually, the resulting investment leakage would cripple Europe’s ability to reach its climate goals. It may mean compromising on climate ambitions or losing businesses that cannot comply with them. A cost-ineffective climate policy is thus a dangerous vicious circle that risks de-industrializing the EU and intensely hurts its long-term prosperity perspectives. It’s time to rethink Europe’s climate policy for good.